Jan 27, 2021

Does animation need a cinema-

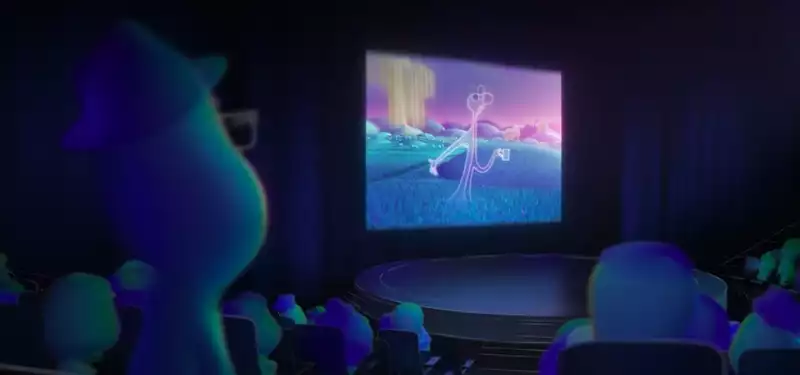

The biggest animated feature to be re-routed from theaters to streaming so far happens to be one of the few films I saw in a cinema last year. I caught Pixar's Soul at the London Film Festival between lockdowns. Although Covid protocols turned the screening into a sparse, wary affair, I was thrilled to see the film in this setting. The sight of myriad unborn souls plunging through a heavenly portal to Earth was so visceral because the portal was up there on the cinema screen, many times vaster than me.

Soul has the design and production values of a film that was expected to play on big screens and gross many hundreds of millions of dollars. Yet it is now a “Disney+ Original.” Of course, by the time its U.S. theatrical release was cancelled in October, the news hardly came as a surprise: for half a year already, studios had been piloting a “new normal” in film distribution, with animated titles central to their strategy.

The first Hollywood title to break the theatrical window in response to the pandemic, back in the mists of April, was Dreamworks Animation's Trolls World Tour. No sooner had Universal trumpeted a successful launch than Warner Bros. followed suit, sending Scoob! straight to video on demand. The Spongebob Movie: Sponge on the Run was dealt a similar fate in June. Meanwhile, Disney released Onward and Frozen 2 on streaming ahead of schedule, after the pandemic cut short their theatrical runs.

These experiments - with animated and live-action releases alike - laid the groundwork for Warner Bros.'s stunning decision to send its entire 2021 slate of 17 features to theaters and HBO Max at the same time. No fully animated films were immediately affected, but the list includes at least three hybrid titles: Tom & Jerry, Godzilla vs. Kong, and Space Jam: A New Legacy.

By imperiling cinemas, this new normal has prompted much discussion of what cinema-going means. Warner Bros.'s announcement drew a backlash from filmmakers, agents, and production companies. Many were anxious about how the move would affect their pay packages, but some, like Tenet director Christopher Nolan and Dune director Denis Villeneuve, passionately defended the theatrical experience in and of itself.

Meanwhile, dozens of top filmmakers signed a letter to Congress, calling for relief for the exhibition sector. The letter made a case for the uniqueness of cinemas: “Every aspiring filmmaker, actor, and producer dreams of bringing their art to the silver screen, an irreplaceable experience that represents the pinnacle of filmmaking achievement.”

The animation industry has been notably quiet in these protests. No full-time animation director signed the letter. This raises a more specific question: what does cinema-going mean to animation-

The theatrical experience has never quite been fetishized in the animation world as it has in live action. The self-reflexive genre of films that pay tribute to cinemas - think Cinema Paradiso, Once Upon a Time… In Hollywood, The Spirit of the Beehive - has little presence in animation. Relatively few animated features are made, and that was even truer until the last couple of decades. Outside the insular festival circuit, shorts are barely shown on big screens anymore.

Yet animated films remain tightly bound to the theatrical ecosystem. In 2019, they accounted for the second-, third-, and fourth-highest-grossing films at the domestic box office. Those three films - The Lion King, Toy Story 4, and Frozen 2 - all took more than $1 billion globally. Streaming can't provide that kind of revenue for any individual film (for now).

Even 2020 has given us examples of animated hits. A pair of titles in East Asia, China's Jiang Ziya and Japan's Demon Slayer movie, helped usher the old normal back in as Covid cases fell and theaters reopened, with the latter climbing to the top of Japan's all-time box office. The Chinese and Japanese markets have their idiosyncrasies; comparisons with the U.S. aren't straightforward. But at the very least, the triumph of these two films challenges the idea that post-Covid audiences, spoiled by streaming, will inevitably lose interest in cinemas.

Is that a surprise- After all, cinemas are unique. The screens are big, the sound rich, the experience communal, the darkness conducive to a special kind of focus. Gripes about skyrocketing ticket prices obscure the fact that cinemas remain cheaper than most other arts and entertainment venues.

The alternative - a good home set-up - is potentially more exclusive: it privileges those who can afford quality kit, and whose domestic situation allows for quiet, sustained leisure time. Under lockdown, this kind of leisure time has, for many, slipped away. Even when the pandemic ends, the retention of work-from-home policies in some sectors could chip away at the appeal of home viewing. I suspect that the more we have to watch screens at home, the less we will choose to do so come the evening.

Then there's the matter of the productions themselves. Housebound viewers were treated this year to a torrent of high-quality home releases. But these weren't streaming films - they were theatrical films redirected to streaming. It remains to be seen how the budgets, pipelines, production values, and general creative approach of animated films will change in the made-for-streaming age, but I imagine we'll notice differences at the higher end of feature production. Will a film with the polish, ambition, and dizzying creative detail of Soul be as easy to make when a blockbuster theatrical run isn't on the cards- I doubt it.

I may be proved wrong in all this. Either way, I'd like to see the debate play out more openly. Does animation need cinemas- Why or why not- These are topics we'll probe throughout the rest of this year.

Post your comment